How do you introduce the guy responsible for much of Dr. Dre’s sound after 2001? During the 2000s Focus… was one of Dr. Dre’s go-to producers, contributing production to artists like The Game, Busta Rhymes, Bishop Lamont, and Stat Quo. After a brief hiatus from Dre’s camp, Focus… returned last year and began working with Dre on Compton. With production credits on six songs from Compton and mixing credits on seven, we thought it was a perfect chance to talk with Focus… about just how big of a role he played in the making of Dr. Dre’s final album. Big thanks to Hatch at iStandard for making this happen.

You left Aftermath in 2008 but circled back in 2014. Why’d you come back?

Focus…: Two reasons. One was that no matter what it is, I’m always gonna love doing music, and Dre is the only person in the music industry that takes me seriously and understands what I’m trying to do with my music, understands what I love to do, and doesn’t put me in a box.

Two, my brother Tyheim Cannon started working with Dre and was trying to get Dre back excited about music. So he wanted to present some music of mine and I didn’t really feel like my music was ready, but lo and behold Dre heard some stuff I was working on and he liked it, so it got him back in working mode.

People that have been following your career can tell when you’ve had a part in a Dre beat, but tell us what Dre looks for from you specifically when you’re in the lab together?

I don’t even think that I could answer that, only because that’d be me dipping into the mind of Dre, but I do know that at the end of the day, my biggest thing with him is that he understands and knows that the most important thing to me is making sure that he’s represented correctly. And I don’t care how I’m represented. It’s not about me and what I’m doing for Dre. It’s more along the lines of what Dre wants from the team, and we have a great team that works over there at Aftermath, so I just do my best to play a part in that team and make sure Dre is represented correctly at all times.

Let’s go through each song you have production credits on from Compton. Tell me about making the intro. That song really sets the tone for the album because while 2001 was cinematic, it feels like Compton is more operatic with the strings and the horns.

I think your perception is dead on. There was a movie with 2001 and with this one we even called the opening intro an overture, and that was by Dontae Winslow and his camp. There was nothing better than to have an original instead of the THX that started 2001. This was something that was original and could be part of the family, so we really appreciate Dontae Winslow for chiming in on that. The next part of the intro that had the commentary on it, that was my original music and I got to work with the likes of Eric “Blu2th” Griggs and Trevor Lawrence. Trevor and Blu2th just added that extra funk to what was going on with the music that I had there, and Dre just directed us. It was one of those things that just came together as a team effort.

Who’s Dontae Winslow?

Dontae Winslow is an amazing trumpeter. He does orchestration. He plays on a lot of the records like “Talking To My Diary,” he plays on the end of “Deep Water,” he starts off “Talking To My Diary” as well. His trumpet resonates throughout the entire album and he’s a jazz trumpeter, but at the same time he’s very into what we’re doing over at Aftermath as well.

We just spoke to Big Hutch about “Loose Cannons” last week. Talk about making that track.

That was really cool. I was going through a folder of samples and it was just one of those days where we were all just jamming together and Dre was wondering if I had any more samples, so I triggered that one. It’s from an old French or Italian soundtrack, and one of the things I know Dre loves is aggression, but just from knowing Dre and knowing how he likes instrumentation, he likes the way trumpets can put across aggression but still be artsy and beautiful at the same time. So when I triggered the sample he was like, “What is that?” And I started playing with it. That second part where it goes into the different time signature that Trevor set off, that was something I had [been] playing with in Logic.

And then I went into another idea with the same sample and Dre said he wanted all three sections. That was amazing to me. I didn’t understand what he was doing because we were just laying down the sample and then he was like, “Put that part down. And put that part down too.” And I’m looking at him like, “OK, this is all gonna be one song?” And he was like yeah. So the real orchestrator, the real conductor of that entire maddening orchestra was Dre. That was all Dre’s outlook, but it was really something that I started because I was trying to get some stuff up for him.

Did Dre play any of these instruments himself on the album or is he more of a composer at this point?

I think right now Dre is showing people what he can do at its fullest capacity, but Dre really gave us a platform to stand on, to showcase our talents on, and to move forward from because we have an amazing leader. We have one of the best leaders in the industry, and at the end of the day he wants all his soldiers to be just as formidable. It can’t just be a great leader and then you have weak links in your soldier ranks, so he gave us a great platform to stand on, each and every one of us that had something to do with Compton, [so we could] stand up and start to build ourselves and the substance that we are as each and every soldier that works for Dre.

Talk about making “Issues” with Ice Cube and Anderson Paak.

Oh my goodness, [Paak] is a beast. When it comes down to “Issues,” I set it off with the Selda [Bagcan] sample and then Trevor Lawrence and Ron Feemster went in and just sent the song into a whole other orbit. Curt Chambers played [guitar] on it and then Dem Jointz came in. I told him Dre wanted to go somewhere else with the hook, so Dem Jointz wrote the hook and then I changed the music for the hook. So it was amazing that that record came together the way it did because it was so artistic but it still had the same drive and aggression as prior Aftermath stuff. So it didn’t stray too far from what we were as Aftermath, but it definitely helped us hybridize what we are now and what we were before.

And “Deep Water,” which is a standout on the album as well as one of three songs Kendrick is featured on. He feels very central to Compton.

The music that starts “Deep Water” is what I had. It was something I was trying to put together and my brother Tyheim was like, “Yo, you need to bring Cardiak in to get the drums that you’re looking for,” because there was a certain feel that I wanted for it. Dre was asking us for a specific kind of track and I knew that I couldn’t do it by myself. I couldn’t just nail it the way he wanted, and I’m all about hitting the bullseye. I’m not trying to be the superstar or anything. It’s not centered around me, it’s centered around Dr. Dre.

So I hit Cardiak, Cardiak came through and nailed the drums. We got the record pretty much formatted, and then Dem Jointz and DJ Dahi came in and put the sprinkles on it and it was a wrap. After we put the record together and Dre heard it, he was like, “That’s what I’m talking about!” He told me to change this piece and move it around and that was it. After that, it just started moving really fast from there.

That’s Paak doing the drowning man at the end. How’d he record that?

It’s amazing that this was something Dre directed. He said he wanted water sounds so me and [engineers] Maurice “Veto” Iragorri and Quentin “Q” Gilkey were finding these sounds. He wanted big bubbles, he wanted it to feel cinematic, and when he brought in the aspect of the drowning man, Anderson came in and performed it in a way I’ve never seen before in my life.

He had a bottle of water, and he was taking swigs of the water, and it sounded like he was literally drowning. His performance on the mic was nothing short of an Oscar-winning performance, so what we did was me and Veto started going through different filters and we would put him in this filter that sounded like he was actually immersed in the water, but that was all just him performing on the mic and then us throwing it through a filter here and there to make it sound like he was going under and over the water.

Was there anything you and Dre disagreed about during the recording of Compton?

I’m not stupid, I don’t have disagreements with Dre. [Laughs] Na, if there’s something I disagree with, that’s because of my perspective, but the main character, the main center, and the main course on this big feast that is Compton is Dr. Dre, so who am I to disagree with what he wants to put across? My job is to play my position and make sure I’m doing a good job at playing my position, so I’d never disagree with Dr. Dre. Ever.

Tell me about making “One Shot One Kill” with Snoop and Jon Connor.

We had a trip in Hawaii and we went out there towards the end of last year. It was just a sample that I had and I treated it with just a little bit of distortion and filters. Trevor Lawrence Jr. chimed in on the drums and just made it very hip-hop feeling, and that’s all it really was, just drums and guitars at first. And we all turned around and started building it up, and Dre dug it. He’s liked that beat since Hawaii last year, he took it downstairs in Hawaii and started laying verses. The excitement around the record happened instantaneously, but for it to resonate all the way up until Compton, that’s probably one of the proudest moments I have on the album.

Yeah that guitar is grungy as shit.

[Laughs] No but the extra added guitar, we have Blu2th on there, we have some extra added stuff with Curt Chambers as well. As big as it got up to Compton, that’s not how it sounded when me and Trevor first put it together, but it’s really one of those things that once Dre gets involved, it’s gonna have a very orchestrated and organic feel.

There’s obviously live instrumentation across the album. There are live drums, right?

Yes sir, Trevor Lawrence Jr. bro. I can sing this guy’s praises all day long. He has a kit, an electronic kit, that he actually triggers stuff through his Ableton. I think he’s using Push now, so he’s able to turn around and do real live fills, like all the hi-hats, snares, everything. He’s not programming it with an MPC or pad, he’s actually playing it as a drummer, and he’s a jazz drummer but his pocket and his hip-hop feel is undeniable and incomparable. So when it comes down to it, Dre would rather him play the way he plays than program. A lot of the stuff you hear that Trevor is on, he played it with his hands, he didn’t play it with the pads, so he’s really amazing.

Yeah there’s that outro with the hi-hat on “All In A Day’s Work.” That’s him?

Yes. And then it goes into “Darkside.” Trevor does that stuff by accident. It’s not even by accident. He does it intentionally, but it’s like…you would never know that there would be a song with a hi-hat solo on it. So he’s dope.

You mention “Darkside” and me and my boy thought the keys on “Gone” sounded like your work.

Yeah…that’s funny. That is Ron Feemster, who also used to go by Nephew. It’s funny you say that, because back in the day I had a lot of people that would compare me to Nephew or compare him to me, so it’s amazing to be able to work with him and even be on the same team as he is. He’s amazing, he’s amazing on keys, he used to work with Michael Jackson. His list [of work] is vast and amazing, and that was him on the piano work [for “Gone”]. That’s really Aftermath’s feel, our whole minor work, making those pianos a dominant instrument. That’s really an Aftermath feel, it’s not so much a me feel, it’s more what we did for Dr. Dre.

The more I talk to you, the more these names come tumbling out. This sounds like a 20-piece band. Give me a sense of how many people were behind the production on this album.

It’s about 17 of us as far as structure, intricacies, nuances. The immediate musical part of it would be Trevor Lawrence (drums), Ron Feemster (keys), Andre “Briss” Brisset (keys), Curt Chambers (bass & guitar), Blu2th (bass & guitar) he’s amazing, and myself, and we also implementing people like Cardiak, DJ Dahi, DJ Kahlil who’s my yoda, and Dem Jointz. So we didn’t stray too far. Even DJ Silk did “Talking To My Diary.” Dontae Winslow did the horns. If you look at us, we were sort of an urban orchestra, if you would.

Let’s talk about “Talking To My Diary” for a second. Dre said he scrapped Detox and Compton was released instead, but we know “Talking To My Diary” was made as early as 2010 because it was in an HP commercial, so the line separating the two albums isn’t as clear as people think. Talk about whether some of Detox bled into this new album.

That’s very observant, yeah. I think people need to realize that Detox was scrapped, but that doesn’t mean all the music was bad. Dre said he didn’t like Detox and he said that on Beats 1 on The Pharmacy, so he let everyone know the reason why it didn’t come out. So from his mouth to God’s ears and the public, he said, “I didn’t like Detox and that’s why it didn’t come out.” But he didn’t say, “I hated all the music that came from Detox.” So when it comes down to it, DJ Silk was the only person that survived from Detox all the way up to Compton. And that record, you know, him, Mr. Choc, and Slimm The Mobster, those are my people and it’s amazing to see that [record] get the light and the love that it deserves. A lot of people are talking about that song because they feel that’s one of the biggest records on the album that is indigenous of Dre’s sound.

It must be funny to see Dr. Dre’s reaction to a record that was clearly from Detox sessions getting so much love now.

No matter what, it’s gonna be a popular record because of the movie as well. Not taking away from the motivation and drive of the record itself, but the fact that it starts the movie and it ends the movie. It’s one of those things that you’re gonna take away from one of the greatest movies that was created in urban filmmaking all the way until now. You’re gonna take it away and it’s gonna resonate with you because they gave you such a clear and present moment with the movie, so it’s a great way for us to end Compton the album as well.

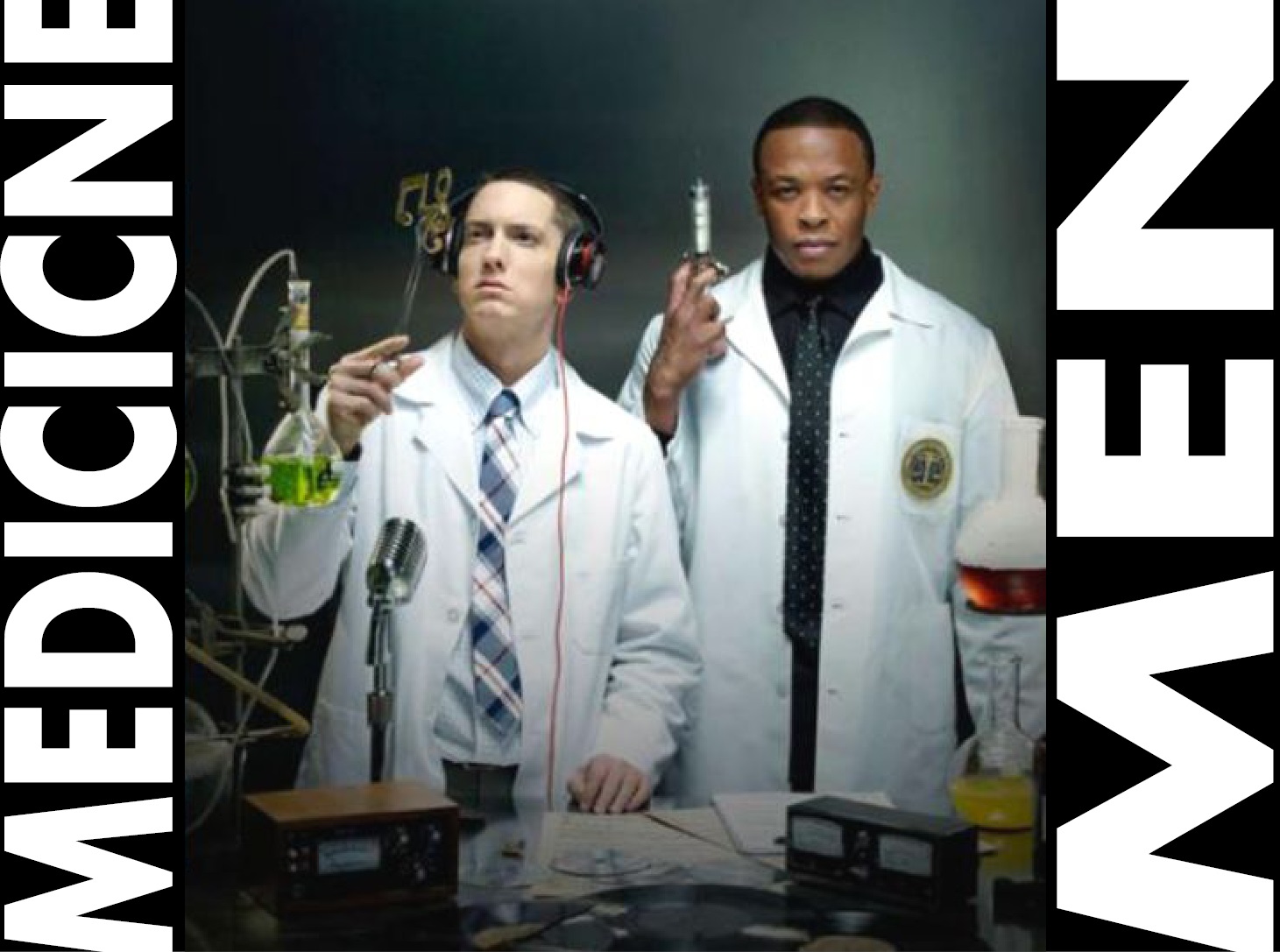

And that brings us to “Medicine Man,” one of the most powerful songs on the album. Talk me through making that song from beginning to end.

I wish I was there at the beginning, I can’t even lie to you. Dem Jointz and Candice Pillay, those are pretty much two of the five biggest stars on the album to me. Dem Jointz is an amazing alien that I’ve had the honor and pleasure of being united with. I got to meet him through Marsha Ambrosius, who’s another alien. I got to connect and work with him, but the record, they already had Eminem in mind and the record was on the cutting room floor, but when it came down to it Dre was like, “I need one more record, because I want to put Em on the album.” So we rallied behind Dem Jointz and Candice to get “Medicine Man” back on the working table.

Dre was like, “Em needs something bigger, it needs to be more theatrical for Em to come in.” So Dem Jointz allowed me to come in. He scrapped the entire second verse pretty much to the end of the record and he allowed me to orchestrate Eminem’s verse, so that’s why I’m on the production on there, because from Eminem’s verse on that’s my music. So that’s a blessing and I got Curt Chambers to come in and play guitar so it got a little bit of that “Lose Yourself” feeling, so I really wanted it to just feel familiar, but at the same time I wanted it to be bigger and better. And not disrespecting “Lose Yourself,” don’t get it twisted, that’s an Oscar-winning record. But you have to turn around and put yourself ahead of the game. I’m not gonna let [“Lose Yourself”] make me feel lower than I can. I was like, “Man I gotta get Eminem on this man. We gotta make it feel bigger and better.”

That was a shining point. That was a fourth quarter, 20 seconds on the clock type of shot, and they allowed me to be a part of that play, so I just appreciate them as well.

That whole section where Em comes in is nuts, so thank you for that. I’ve seen people saying they thought you turned up the volume when Em drops that crazy part.

Na when it comes down to it as far as mixing is concerned, everybody that knows Dr. Dre [knows] there are certain nuances that are…not going to be divulged, but these are things that make his records a direct fingerprint of who he is as a producer, and when that record does come in and those drums come in, because the initial strings that introduce Eminem were maniacal and I had them louder than what they are, but Dre knew exactly what needed to be introduced and what time it needed to be introduced and what feeling and what level.

All of that stuff is Dr. Dre, man, but as far as a volume rise and things like that, that’s all a part of a great mix and Dre understood that when it comes in, there’s gotta be a certain aggression. When the drums drop, there’s a certain aggression that happens because if you listen to Em’s verse, there are three levels of aggression. He doesn’t come in soft. He comes in aggressive, he gets more aggressive, and then there’s this absolute aggression that he rides up until the end where it says, “Fame and fortune.” So it’s amazing to introduce those stages and [have it all make] sense to every listener.

Did you see Em record that verse?

No, Eminem did that in Detroit so it was almost like Christmas [when we got it]. You walked downstairs and there’s a gift under the tree and you just wanna rip it open. So every time we got an email from Eminem and we got to hear what he was doing, it was really amazing. That was an amazing moment.

What’s the best song that got scrapped from Compton?

I’m not gonna call it the best song, but one of my favorites that was left off of Compton was a record that was produced by Siege Monstrosity and it was called “Naked.” Hopefully that’ll see the light of day but that was really one of my favorite records, and [Siege] is one of those producers I get inspired and motivated by.

Those who have followed Dre’s career know he’s always been a dark dude musically. Why did he kill that woman at the end of “Loose Cannons”?

That’s another question that would be getting into the mind of Dr. Dre and I’m just not an occupant in that place, but I do know that Dre, Eminem, 50 Cent, Game, everyone understands that all publicity is good publicity, from the days of N.W.A. all the way up ‘til now. And if you’re gonna turn around and talk about it in a good or a bad light, you’re gonna talk about it, and that’s what’s important to [Dre]. I wasn’t there, I didn’t have anything to do with that part, but I do know he’s like a Martin Scorsese of music and those things matter to him, to make people be aware.

Even the drowning guy, if you look at it for what it is, you’ll say somebody is drowning, but if you listen to it artistically, if you get in over your head anywhere, you’re pretty much drowning, right? Doesn’t mean literally, but if you listen to the song it’s telling you, “You come to Compton and you don’t know what you’re doing, you’re in over your head.” So people are listening to it for face value instead of understanding that it might be artistic.

Throughout the years, we’ve seen a lot of people come into Dre’s Aftermath camp, and we’ve seen some stay and some go. You’ve done both – you came, you left, and now you’re back. How’d you manage to stick with Dre while so many others have fallen by the wayside?

I think that everybody who has gotten with Dre gets this veil over their face thinking that once they get with Dre, they’ve made it, and that’s really the beginning of the race, that’s not even the finish line. When you get with Dre you really have to show and prove who you are and what you’re gonna bring to the table because Dre doesn’t really need anybody. He can have anyone he wants on the team and it really is one of those things where if you don’t look at it as what it is, a blessing, and do the best you can every day, all day, even when you have four or five different records out, you need to show him that you’re not a waste of time, a waste of effort, a waste of money.

One of those things I always wanted Dre to understand, being a worker bee, was that I’m here to be the best worker bee you have. I’m not here to be everybody’s best friend. I do want to befriend everybody because everybody becomes family, but I want to be the best worker bee you have and if you give me the opportunity, I’m gonna show you what I can do. And two Grammys later, over 30 million records sold worldwide, that’s always been my make-up. That’s always been what drives me to make sure Dre understands this isn’t something I take advantage of. This is an opportunity that I don’t look at lightly and I guess that’s why I was able to speak to him and come back into the building to work at the capacity I’m working in. He knows I’m a team player and I’m never gonna turn around and make the whole thing about me. It’s about Dr. Dre and I’m just honored to be there.

What’s one production tip you took from Dre that every producer should know?

Be aware of what you’re doing. I think a lot of people want to put out music just to be putting out music and they’re so busy trying to follow a trend and not focusing on the fact that music is something that’s gonna take a little bit of time and effort. For Dre to say he didn’t like Detox and sit out for 16 years and then make Compton, he knew it would take time and effort and motivation. Don’t rush and just put out music just to put out music. Put out great product.

Dre taught me to be meticulous, he taught me to be articulate, he taught me to pay attention to detail. Dre taught me there’s no reason for me to rush it, because I’m the artist and if I rush the Mona Lisa then the Mona Lisa wouldn’t be a Mona Lisa. Even for him to say, “Would you stand over Picasso’s shoulder and tell him about his brushstrokes?” A line like that, he’s likening it to art. This is great art that he’s likening his music to, so for him to appreciate and acknowledge that this is an art, I took that all from Dre, and like I said in every interview I’ve ever done, he’s one of my biggest mentors and biggest influences. If it wasn’t for him, there’d be no me. Him and my father.

In terms of mixing, he taught me you don’t have to muddy everything and put it down the middle. Playing with your sounds, you have left to right, you can push it even further. Dre mixes in surround sound so he understands the sound field way better than most producers I know. If people listen to Jay Z’s “Minority Report” and they listen to the intro with the helicopter, they’ll understand what surround sound is. And that’s just a helicopter. Especially being an urban producer, they’ll try to pigeonhole him, but Dre is really one of this generation’s Quincy Jones, and that’s why I look up to him.