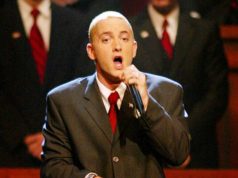

LL Cool J released a book described as the definitive volume of the most important origin stories from the last fifty years of hip hop, including one from Eminem.

Penned by the iconic figure in hip hop, LL Cool J, in collaboration with journalists Vikki Tobak and Alec Banks, this tome commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the influential culture, resounding beats, and foremost voices within American hip hop music.

Titled “LL COOL J Presents The Streets Win”, this work pays homage to the birth, ascent, and evolution of hip hop culture, underlining its unquestionable impact on American music throughout the last half-century. Within its pages, LL Cool J guides us through the odyssey of this musical genre, capturing it through a treasure trove of rarely-seen photographs that document its inception—ranging from electrifying block party performances to candid street snapshots, vibrant parties, intimate recording studio sessions, and much more. These evocative visuals are interwoven with personal narratives, generously shared by hip hop’s MCs, B-Boys, graffiti artists, and DJs, who divulge their own stories of falling head over heels for hip hop, their remarkable entry into the industry, the wellsprings of their artistic and personal style, and their profound insights into hip hop’s culture and music. Within the pages of this work, luminaries such as DJ Kool Herc, Salt-N-Pepa, MC Lyte, KRS-One, Eminem, Mary J. Blige, Grandmaster Flash, Run-D.M.C., Beastie Boys, De La Soul, Slick Rick, Public Enemy, Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, Nas, A Tribe Called Quest, Big Daddy Kane, Fat Joe, DJ Khaled, and many others share their remarkable stories.

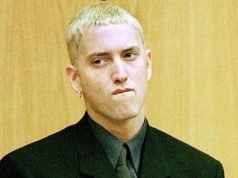

Of course, there is a story from Eminem. Right there, on page 216.

EMINEM

I was probably eleven or twelve years old when I wrote my first rhyme. I was at my Great Aunt Edna’s house, and it sounded exactly like “I’m Bad.” One rhyme sticks in my head: “Something before you can blink, I’ll have a hundred million rhymes, unlike a ship, you first rhyme. will sink.” That was my first rhyme.My homework was hip hop. I didn’t go to school. I would rather just rap, and that’s pretty much all I did. I watched LL COOL J, Run-DMC, Beastie Boys, Big Daddy Kane, Kool G Rap, and Masta Ace. It was the wordplay. It was also interesting to watch LL COOL J and see his range as a writer. He could make a love song, and he could make a song for the dudes.

I did a lot of rapping in the basement. I had to get to a certain level before I would let anyone even hear my raps. When I started realizing that some of the stuff that I was writing was maybe not as good, but almost as good as certain rappers, it gave me the hope that maybe I could actually do it.

When compound syllable (a style of rhyming) came into play and I started hearing LL COOL J, Kool G Rap, and Kane do it, I was just like, “Holy shit, they’re not just rhyming the last word. They’re rhyming every syllable of that word.” When I started doing it, I was everywhere. I went to open mics. Proof took me to a lot of places because he didn’t have a job back then. He just rapped and went everywhere.

I met Proof on the steps of Osborn High School in Detroit. I handed him a flyer to a talent show, and he was like, “You rap?” And I was like, “Yeah, I rap.” He was like, “Why don’t you say something?” I was like, “Okay.” So I did a rhyme with “birthday” and “first place.” Then he did his, and he rhymed those same three words. I was like, “Wow, we both understood compound syllable rhymes.” Then, he showed up to the talent show, and I was like, “Holy shit. He showed up. Okay, cool.”

Toward our early twenties, Proof was in every rap spot there was. I had a job, so I couldn’t do everything that I wanted to do. His buzz around the city was incredible. One day, he called me when I was living upstairs in the attic of my ex’s mom’s house, and things weren’t looking so good. I had stopped writing for a while, and I hadn’t talked to him in four months. He was like, “Yo, I’ve been doing this, this, and this. You need to come up to the hip hop Shop.” And I was like, “Okay.”

I had a day to write the rhyme and try to memorize it by around six o’clock the next day. I rapped and got a reaction. I was like, “Shit, I want to do this. I’m going to write a rap every week and come up here.” That’s what started happening. And then I threw my hat in the battle ring and started doing that and won the two battles there.

Proof used to take me to the Osborn High School lunchroom to battle. He would say, “I got ten dollars on the white boy.” I would win, and he’d get the money. Being white in that setting was a challenge. It wasn’t easy. I was definitely the elephant in the room. But me and my friends — Proof and Denaun — we saw color, but it just didn’t matter to us.

After I started winning battles in Detroit, I felt like I should take it out of the city and try to make a name elsewhere. I started getting in competitions like Scribble Jam. Eventually, Mr. Porter and I went to ’97 Freaknik to handout tapes because my first album Infinite didn’t do well at all. At some point, I went to the Atheneum Hotel in Detroit because Bizarre from D12 told me about this woman named Wendy Day. He was like, “Yo, you need to give your tape to Wendy.”

Giving Wendy Day the tape changed everything. Two weeks later, she called me and was like, “You have restored my faith in white rappers.” And I was like, “Thank you. Cool. I’m not sure how to take that, but I’m sure there’s a compliment in there somewhere.” The fact she called me was incredible. Every time I would be at the breaking point of giving this shit up — because it just seemed to be going nowhere — I’d get a little spark that would keep me going just a little bit more. Wendy wanted to put me on her five-man battle team for the Rap Olympics.

I had just got evicted from the house I was staying at literally the day before I was supposed to go to the Rap Olympics in California. I pulled up to the house and found all our shit was on the front lawn. People were going through it. I didn’t have much to grab, but I put it all in my car. Then I had to break into the house through the back door. I slept on the floor, and Paul Rosenberg was my wake-up call the next morning.

There was a solo battle before the actual team battles of the Rap Olympics. The winner got five hundred dollars and a Rolex. I jumped in that battle because I needed that money because I didn’t have a home to go back to. I ended up going through everybody in the battle and faced a guy who had a buy-in straight to the semi-finals. I got the mic, and this guy I’m facing walks behind the video screen. I had nobody to battle. I couldn’t talk about his shoes. In hindsight, I should have said something like, “You’re scared. That’s why you’re hiding behind that screen.” But in the moment, I didn’t know what to do. I tried to mix punchlines and written shit with freestyle shit, because I had watched Proof do that. He was masterful at it, but I choked.

The guy came from around the screen and got in my face. I don’t remember one line he said, but he was screaming in my face. Everybody was like, “Yo, he’s killing him. He’s killing him.” But I had already choked, so it really didn’t matter what the guy did.

I lost. At that point, it was looking really bleak. Then, this eighteen-year-old kid, Dean Geistlinger, came up to me and said, “Yo, man. Can I get one of those tapes?” I just kind of threw it at him — like, whatever. At the time, I didn’t know that he worked at Interscope. He ended up giving the cassette to Jimmy lovine. I heard the story that Dre had come over when the tape was in a bag and he asked about it.

I bought a used ’93 red Camaro with some of the advance I got from signing with Dre. I sent some money home to Kim, and then I bought that Camaro for like $1,200 bucks so that I would have a car when I came back. I did my first interview with Rolling Stone with Anthony Bozza. He wanted to know where I lived, and I was like, “Well, I’m between touring and shit like that. I live in this trailer.” He wanted me to take him to it, so we pulled up in my red Camaro. I go to walk in the trailer and see an eviction notice on the door. I broke in through the window to open the trailer. It had been cleaned out, and all my shit was gone.

When I first got in the game, I didn’t understand a lot of shit about fame. I didn’t understand that when you are walking outside the venue after a show, there’s always going to be somebody that you don’t have a chance to get to. It was my first experience with it. It was like, “What the fuck is this?” People wanting me to sign shit — I don’t get it. It’s a signature. I didn’t understand it.

I think “Stan” was a combination of what I was going through at that time, experiencing fame for the first time and all that stuff. When I got that beat from Mark “The 45 King” with the Dido hook on it, I was just like, “..but, your picture on my wall.” I just pictured it. That’s what I did as a kid, and how I felt when LL COOL J and Run-DMC first came out. My walls were covered up to the ceiling with pictures from Word Up! and every rap magazine there was. I put myself in the shoes of worshiping LL COOL J and Run-DMC but thought, “How could somebody worship me?”

The book is already available in the US and Europe and we have a dedicated fan to thank for sharing pages relevant to Marshall’s story.