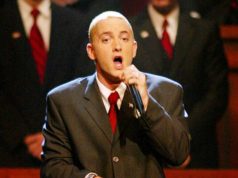

Eminem’s highly-anticipated eighth studio album, the Marshall Mathers LP 2, officially dropped yesterday, and Billboard is already projecting it to be his seventh straight No. 1 album and the second-highest debuting record of the year. But there have been a number of elements in the buildup to this release that have made MMLP2—the followup to 2010′s Recovery—a much different Eminem product than what fans have seen in the past.

Much of that can be attributed to the work of longtime Em manager Paul Rosenberg, who has helped guide Marshall’s career since 1999′s Slim Shady LP announced his arrival on a major scale. His followup to that, 2000′s original Marshall Mathers LP, was a massive, diamond-selling statement, which saw Em pushing back against the critics, his mother, fame and his family life, all in one dazzling explosion of emotion, raw rapping and songwriting brilliance. So when Em announced this new record would be the second in the Marshall Mathers lineage, it opened it up to direct comparisons lyrically, thematically and, in a radically different music industry, promotionally. XXL spoke to Paul Rosenberg last week about MMLP2, the marketing rollout that saw Em do spots on Saturday Night College Football and with Call Of Duty, and how the character of Slim Shady has changed over the past 13 years.

XXL: When did you guys get started working on the album?

Paul Rosenberg: Well, Em is always recording whenever he gets the chance; that’s sort of what he does on a day-to-day basis when he’s not out doing shows or whatever the case may be, he’s in the studio. It’s kind of a continual process, but I would say he really became serious about focusing on it and figuring out when he might want to put it out sometime around early March, 2012.

When he first started did he know he wanted to make it the second Marshall Mathers LP?

No, I don’t think so. I think it’s something that came into focus earlier in the process than it usually does—meaning the title—but I don’t think he started off before he recorded anything saying, “This is what I’m gonna call the album.” I think it’s a concept that came out of the work he was doing.

How was it different than any of the other albums that he’s put out?

How was it different? Well, it’s the first time he’s ever done an album that’s a continuation of another album, so it’s different in that sense. I think it’s the first time he reached back and decided to revisit some of the themes that he had explored in some earlier records and give them a continuation. When he talks about the album he doesn’t talk about it as a sequel, he talks about it as a revisitation.

It seems like some of the emotions are flipped—well, not necessarily flipped, but different…

Well, you know what it is? It’s not that the emotions are different at all, it’s that you’re dealing with a person almost 15 years later and their perspective on some of the same themes. And obviously that’s gonna change for anybody, but specifically for him, who has been through so much in that 15 years, that you’re looking at things differently. So I think what we’re getting to hear is a guy who has had 15 years of life experience as an adult since he’s recorded these records when he was 25, 26, 27 years old. And it’s a very different perspective.

It’s fascinating, too, looking at the two albums side-by-side. His delivery is more mature, but there’s still a lot of—I don’t want to say anger—but the raw emotion that he’s so well-known for.

Yeah, I think that’s definitely the thread that connects the two projects. And you’re always gonna get that from Marshall, he wears his heart on his sleeve when he raps, and you’re always gonna feel what he’s going through and talking about. I think that’s one of the things that makes people connect to him so much, is that they feel something when they connect to his music, and they can relate to his emotions, even though it may not be the exact circumstances you’re going through, you can always relate to [it].

Was there any pressure coming off such another massive album with Recovery and then the inevitable comparisons that were going to come with making this a part two? Was there any special pressure?

Yeah, there’s always pressure; he’s achieved a level where the expectations are always going to be high. So yes, there’s pressure from those expectations, but we just try to do our best to make the right record for him at that time and what he’s doing creatively, and support that vision. My job, really, is to support that vision and figure out the best way to market and promote it.

He talks a lot on the album about the difference between him and Slim Shady. What’s the biggest difference you see between Slim Shady on this album versus the first Marshall Mathers album?

The difference between Slim Shady on those records? That’s an interesting question. [Laughs] I think back then, Slim Shady was connected to a younger guy who didn’t have the same perspective, going back to what I said before. And now it’s connected to a person who is older. So I don’t know if he definitely has more of a moral compass, so to speak, as a character, but I think Slim Shady thinks a little more now, as a character.

How did you guys get Rick Rubin involved?

It started off with Rick wanting to produce tracks with him. I had had several conversations with Rick over the course of the past few years—I had met him through some mutual friends—obviously, we’ve been a longtime fan of him and his career and what he’s done. After talking to him and learning how interested he was in potentially working with Em, it was just about finding the right time and the right project. So one of the things that I keep pointing out to people is that prior to Recovery, Em didn’t really work with a whole lot of producers. He worked with Dre, and he produced his own stuff himself and his small crew of people that he worked with, and that was it. So moving forward with Recovery, for whatever reason he opened the door up a little more and realized that he enjoyed the experience of working with more people and keeping it a little more open. So it was really about timing, and the timing worked out because he had just opened up to that concept. So the difference from working with Rick and a lot of other producers who may just send tracks is that they went into the studio together and created the stuff that they had made from complete scratch. There was no pre-existing beats, there was no pre-existing anything, there was just a couple of guys going through break beats and seeing what moves the needle for them.

And it’s crazy hearing some of the songs that have come out, the way they put it together. Some songs have four, five, six different parts to them, and that’s wild.

Yeah it is. Part of that is the stuff they sampled. The Joe Walsh record, “Life’s Been Good,” [on the Eminem track “So Far”] has all those different parts in it naturally. But then the thing I think is so awesome about “Berzerk,” it really sounds like something that could have been pulled from the License To Ill sessions from The Beastie Boys, especially with the way that the beat changes and these sort of random breakdowns and variations in the beat. It reminds you of something like “Hold It Now, Hit It” or “Slow And Low” or something like that.

How did you pull together the marketing rollout? You guys had the Call Of Duty placement, and then the College Football appearance—were you trying to get the biggest possible platform with those?

It’s not really about being on the biggest scale possible ever. It’s about doing things that make a lot of sense and that have some sort of connection to Eminem and his fans. So when we look at what the possible partners might be and the ways to creatively—or as they call it, strategically—market the album, we look at things like Beats, because there’s a natural relationship obviously with Eminem and Beats, being that it’s Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine’s brand, and they’re the guys that put him in the game. [Based on] the obviously long-standing relationship that they have, nobody’s gonna look at that and say, “Oh, that’s weird.” And then similarly, with Call Of Duty, not only have we done stuff with Activision in the past with the DJ Hero game we did with them through licensing music and being involved with previous Call Of Duty games. But when they do research for their fanbase—and trust me, they do a lot of it—they continually get feedback that Eminem is one of the most popular, if not the most popular artist for their fans. So when we can connect to that fanbase through something that they love with a game like that, it makes total sense as well. But then also, those are bigger-scale—and obviously with Call Of Duty being the biggest entertainment property in the world that’s a big benefit, and of course we look at that—but also, it just has to fit. So we had this song “Survival,” which is just a natural fit for a game like that, so that makes sense, too.

And then it’s not just about being big, because we’ve done stuff with things that have been on a smaller scale. But when we talked about ways to do things differently… And that was the outset from the beginning; okay, we know how to market and promote a record, obviously, but how can we do it differently?

Do you remember how you’d worked the original MMLP?

I mean, it was very traditional; I don’t even remember us having a marketing partner for that album. Back then, that was kind of less common, frankly. And because the industry was twice the size it is now, there was more money. And when there’s more money, you don’t have to necessarily look for more ways to be more creative. And I’m not saying that Eminem albums don’t generate a lot of money, I’m saying that the extra dollars to just throw around don’t exist as much as they used to.

How else has the music business changed for you in the past 15 or so years? Is that mainly it—you have to get more creative?

Well, you know, I look at it like this—there’s two separate things, there’s the music business and then there’s the record business. The music business is doing fantastic; the record business is having problems and we all know why, and it’s half of what it was 10 years ago, maybe even less. So when we approached things in terms of selling a record, yes, we have to look at things differently and have to be more creative sometimes, ’cause we can’t do all the stuff that we used to do, and we can’t take the things for granted that we used to be able to.

It’s incredible—Recovery still went platinum in two weeks. Em still moves records like that.

Yeah, on a very consistent basis. He’s got an amazing fanbase that really connects with him, and I think that the interesting thing about him is that he doesn’t just have this sort of static fanbase, but he’s still continuing to grow new fans. He’s an artist that has kids that like him that are 12 years old and adults that like him that are 40 years old. So it’s really broad.

via [xxl], by Dan Rys (@danrys)