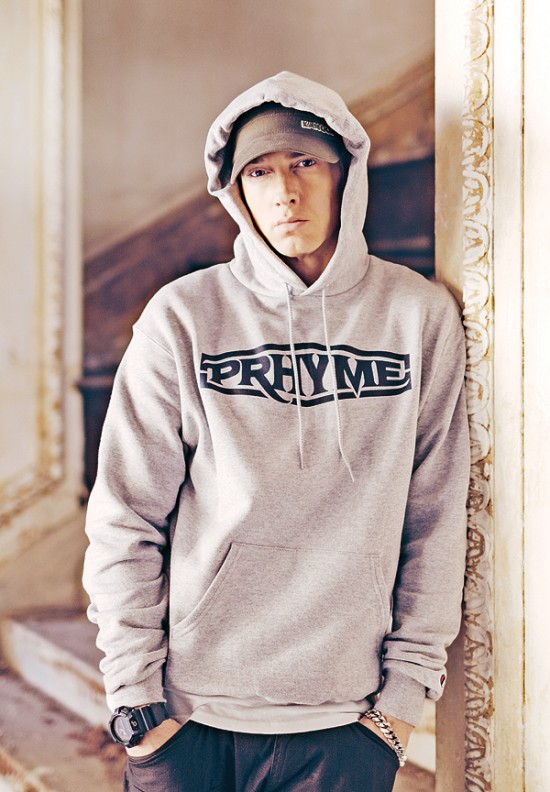

Marshall Mathers III is, arguably, the greatest American wordsmith of the 20th century. He is easily the greatest of the first 15 years of the new millennium. He bends words to rhyme with each other when they shouldn’t. He takes truths that are horrifying, and with his uniquely Michigan sense of humor, finds the funny in the fatalistic. His is the ability to take the world by the balls and spit passion in its face, and we end up squirming and looking at the world a little bit differently as a result. We love him for it.

Eminem, as Mathers is more commonly known, has an attitude and rhymes that are often labeled misogynistic or vulgar, yet to the keen listener, are a reflection of what we all see, for better or worse. He’s not gonna paint a pretty picture, or subscribe to positive mantras when the world is infuriating.

What’s more, he has achieved a level of fame and respect unparalleled for a white American hip-hop artist in the black community. He’s attained a status among African Americans that cannot be purchased or forced. The respect he receives is hard-earned, genuine, and rare. No one in hip-hop will knock him: He is the best.

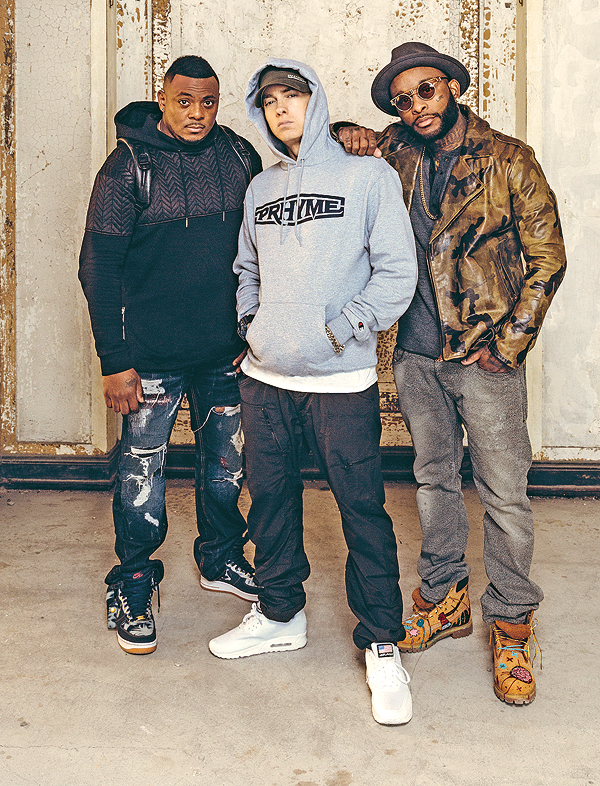

To top off his achievements in the rap world, he does something that most in hip-hop and entertainment simply do not: He uses his fame to showcase other talent. Often, Detroit-born and -raised talent. He provides a platform for that local talent to shine alongside him, as if to say “Look here and listen: these people matter, too” — something unique in an industry flavored with beefs and ego.

And indeed, Mathers’ people do matter. On Shady XV, a two-disc celebration of the 15th anniversary of Shady Records, founded in 1999, Mathers gives nods to where he’s been and to the current landscape of Detroit rap. And through him, that landscape is popping: Dej Loaf, Trick Trick, and Danny Brown, among many others, all make appearances on the anthology.

Shady XV, you see, isn’t Eminem’s greatest hits — it’s music released on Shady Records. One disc of old Shady music, with a little bit of the root from every era of the record company on it, and one of new music, with artists on the Shady label “having a grand old time at the opera,” as Paul Rosenberg told MT.

Mathers and Rosenberg, both co-founders of Shady, sat down with MT in their metro Detroit studio, along with XV artists Denaun Porter, aka Mr. Porter, and Ryan Montgomery, aka Royce da 5’9″, to talk life, Shady, and 15 years of lessons learned.

“It’s a good thing to be a part of a crew of people that can actually stay relevant without trying to go too far outside of what they do,” Mr. Porter tells us. “We all speak about our personal lives a lot, so it’s always something to talk about.”

“I think that in order to stay relevant for a long period of time, you obviously have to adapt,” Rosenberg says. “And in order for people to still be interested, you can’t adapt so far outside of who you are that people go, ‘Eh, well, I don’t like this anymore.’ It’s a bit of a tightrope act, but I think these guys as artists have done a tremendous job of doing it.”

It’s a good point to make — Mathers and company have evolved, but not so far from their roots as to disorient anyone, or cause a backlash.

“I was able to watch the growth from Day One,” says Royce. “The music was a reflection of where these guys were each time they dropped something all the way up until Em got sober. The Recovery album was basically a reflection of him being sober and him changing his life. Watching that and watching his fans grow with him was pretty amazing.”

We ask, rather tongue in cheek, if the crew will ever break out and do some pop dance music, with Usher or Pitbull. Mr. Porter, perhaps surprisingly, says he’d like to spread his wings, both as a producer and as an artist. “I think I’m more open to a lot — like, singing is becoming a thing where I like it a lot more. I didn’t before. Eminem had to force me to sing the first time.”

“Because he can sing,” Mathers stresses. “He just doesn’t like to do it, but he can sing.”

“I was scared to, but now I like it a lot more,” says Porter. “So for me, it’s like, I’m having a lot of fun trying new things, but then finding myself. You have to grow that confidence.”

“But you’re not doing anything that’s still not core to who you are,” Rosenberg says to him. “We’re not going back to — not to single out any names — but I don’t think Marshall or Royce are going to do an EDM Bad Meets Evil album, because that’s just not who they are.” The crew laughs a bit and acknowledges Pitbull’s skills, and that they respect pop and dance, even if they aren’t going down that road.

Life

After so many years in the hip-hop game, and all that comes with it, we ask the crew to share the life lessons they’ve learned.

“I learned to try to find a balance,” says Royce. “I decided to move to New York as soon as my first son was born, and I decided to just live there and not come back until I got a record deal. I’ve always had a live-out-of-the-car mentality.” He says that is “extreme behavior when it comes to the music. As I get older, I’m learning to find a balance — not to give hip-hop 100 percent of myself, balance out my family time, and everything like that. I learned that lesson through music, through hip-hop. Had I worked at a factory or something, I don’t know. My perspective would be completely different. Hip-hop has taught me that: balance.”

For Mathers: “Obviously the biggest thing was not to do drugs.”

“The one thing for me,” says Rosenberg, “is nothing lasts forever. While you’re in those moments that things are really great, to try to step back and take perspective and really appreciate them. I’ve learned to do that.”

“I didn’t have my ducks in a row at an early age,” adds Royce. “I was doing music as kind of a hobby when I met Marshall, and he kind of put me on his back and pulled me into the industry and this ended up being my profession. I just was going with the flow, not really thinking about the future too much. Just living in the moment.”

“I think that all three of us probably had that mentality to some degree just like,’yo, we don’t know anything else,” Mathers says. “This is what we know. All we know is music; it’s all we love and are passionate about. So, I think that, I mean I, for sure, was like, ‘I don’t have nothing else if I don’t do this.’ There’s nothing else I would even care about doing.”

The crew also says that they’re a lot more understanding these days, attaining a level of maturity and sobriety that keeps Mathers from punching people out. But then, they note, their asshole filters are also a lot better, which helps.

Detroit Hip-Hop

Detroit hip-hop, Royce says, is “more advanced than when we were younger. Kids have a lot more opportunities to get on, I think. We started off where we were just fighting to get on the radio, and I see Detroit showing a lot more support than when we first started. To hear a song on the radio by Dej Loaf and Big Sean, people like that … [to know] they’re working or they have opportunities. I think they’re growing here. I feel like Detroit always had some of the illest emcees.”

“We’ve always had talent here,” says Mathers. “But we’ve never really had the platform or the ability to — there’s so many more outlets now with the Internet and things that these kids can create opportunities for themselves. Make a hot song and put it up. You can make a name like that. With us, when we were first coming up, it was like, if we don’t get some kind of song on the radio here in Detroit, we’re fucked.”

“I think Detroit hip-hop today is really balanced,” says Rosenberg. “I think that, when you look at the type of artists that are not just locally but are nationally recognized, you can get a good view of what’s really here. You think about people like Eminem, Big Sean, Royce, Danny Brown, even Dej Loaf now, who’s got some national radio play — that’s a really broad spectrum of artists. It’s great to see that. I think that Detroit’s recognized as a scene now, and I think that back when we were first coming up, that was our goal: to make it recognizable as a scene, so I think we accomplished that.

“When people think about a Detroit emcee, I think the first thing they do is respect the idea, because they know it’s going to be somebody who can really fucking rap,” Rosenberg continues. “Someone who can come for your head and who’s real, and it’s not going to be any fake shit.”

“And I don’t think it’s any particular style that they associate it with either,” adds Royce. “Probably the closest that it’s been since the Motown era just in terms of variety and notoriety, all the different moving parts. And the unity. Everybody’s supporting each other as well. It’s good right now.”

And New Detroit

The group has some perspective on the rapid changes of Detroit.

“We should be happy they’re not talking about a murder rate and all that,” says Porter. “I’m happy they’re not talking about that. That was like, the worst thing.”

“You can’t just put businesses [downtown and in Midtown] and expect everything else to change,” says Rosenberg. “There’s got to be more. It’s a good anchor and a good draw for people to come to Detroit, spend time there, spend money there, live there, and I mean in downtown and the city, but that doesn’t necessarily change the surrounding areas, the surrounding communities. That money needs to be put back in to fix those kind of problems that Denaun just mentioned. You can’t just open up stores and expect people to stop shooting each other.”

“I would love to see them put some more,” says Porter. “I’ve spoken a couple times at schools, and I really would love to see them put more music programs back into the schools. They took that away and that was like, that was something that I think that got us all really started. When you lose that, all you have is sports. There’s so much more to life than just that. Art in general. Taking the arts away from schools: that’s a bad thing. If anybody is trying to bring anything to the city, I would definitely love to see that.”

We ask if there is anything they want Detroiters to know.

“It’s just hard, if not harder, to maintain something than it is to get it in the first place,” advises Mathers. “When you struggle for so long and you worked so hard to get something, once you get it, you have to keep it. You can’t slow down; you can’t stop, you know what I’m saying? You have to work. Sometimes I feel like I work almost twice as hard to maintain it than I did to get it. Me, 15 years ago, I had to put myself in that mind frame to really remember or try to remember how I felt, but at the same time I feel like I work at least as hard to maintain, and I think we all do. To know that it’s possible to have something last if you keep at it, you know. You can’t just get it and be like, ‘Oh, I’ve got it,’ and try to put out one album and be like, ‘I don’t got to do shit now. I’ll just coast through my next one’ or whatever.”

“That’s how you don’t make it to 15 years,” adds Rosenberg.

“That part is cool,” says Mathers. “Being able to be blessed to do that.”

“Totally blessed,” adds Porter.

White Men Can’t Jump

We ask if, when they first met each other two decades ago, they thought they would be where they are today. They all laugh. “I had different goals,” says Royce. “I probably, at that moment, wanted to have a better verse than somebody or something. ‘Maybe I can out-rap Canibus one day,’ or something,” he laughs.

“Do you still think you’re going to be able to out-rap Canibus one day?” asks Rosenberg.

“It’s a toss-up,” is Royce’s answer, with a smile.

Back then, says Mathers, “It was whatever was going on at that moment and trying to be the best rapper that I could possibly be.” His focus, he says, was on that.

“Your dreams get bigger after you do things,” says Porter. “But what we wanted to do? It was a lot smaller.”

“The goal was to not have to struggle and work regular jobs,” says Mathers. “‘Man, if we could just make a living. Just do some shows and get paid a couple hundred bucks a night or something, but do what we love to do.’ And just make enough to just get by and make a decent living, that’s all we really cared about.”

“If I made what a painter makes and was getting paid what a painter made doing what I was doing, I made it,” says Porter. “That was it.”

“Hopefully what we’ve done is somewhat inspiring, you know?” says Rosenberg. “Marshall and I — I’m not from Detroit proper, but I’m from the Detroit suburbs, Marshall’s from Detroit proper — we’re just a couple of guys who really were extremely passionate about music and created this globally recognized brand from nothing. Hopefully people can see some inspiration in that and be inspired the way that Marshall and I were by things like Def Jam, by things like Aftermath, to be able to create their own version of that.”

We ask how everyone first met, and the men get excited reflecting. “Eye-Kyu told me that Em needed some beats, and I had been doing beats for like, three or four months,” says Porter.

“We found out, once we were introduced, that we pretty much grew up fucking five blocks from each other,” says Mathers. “He lived on Rowe and I lived on Dresden and it was, like, five blocks down the street.”

“I would walk past his house all the time to go to school,” adds Porter.

“But we never knew each other,” says Mathers.

Rosenberg asks if Proof had known both of them.

“I was skipping school at the time,” says Porter, “and Proof came up to high school and he was like, ‘Oh, man, this white boy came up here and out-rapped everybody.’ And it was him!”

“Proof used to sneak me in the lunchroom sometimes,” says Mathers with a sly smile. “We would go up to Osborn [High School] and I would rap in the lunchroom and battle.”

It was kind of like a cipher, Porter explains.

“It was kind of like that,” says Mathers, “but whoever had the best verse, Proof would put money on or whatever.”

But Rosenberg has a slightly different take:

“Didn’t he try the White Men Can’t Jump trick with you?” he asks.

“He made a lot of money in school like that,” Porter says with a laugh.

“Proof saw White Men Can’t Jump and used Em as Woody Harrelson to his Wesley Snipes,” Rosenberg explains.

After so many years, the artists carry a demeanor of comfort, filled with gratitude for what they are achieving — gratitude especially for Detroit.

“I think we all really appreciate the support this city has given us throughout the years,” says Rosenberg, “and we try to give back. We try to do things here that other cities don’t get like when we go and do this tour that we did with Rihanna, we only did three cities and Detroit was one of them. Detroit’s not the biggest market in the country, but we want to make sure we do stuff at home. We’re always focused on doing stuff here, and we appreciate all the support that the city’s given us, especially our fans.”

“That’s what we’re thankful for,” says Rosenberg. “Detroit.”

And to that Mathers closes out our interview with an “Amen.”

Shady XV is available on Nov. 24.